By Sateesh Venkatesh – PhD student, UCSD

The air is fresh, there is a light dew on the leaves, and the first shafts of the morning sun pierce the tree cover as our team heads out to the field. These calm mornings in the field typically start the same way, but they disguise the complexity and challenges faced at night by many of the farmers we are off to meet. Mornings for these farmers mean an interlude between nights spent defending their crops from elephants and days of hard work maximizing the production of the same crops.

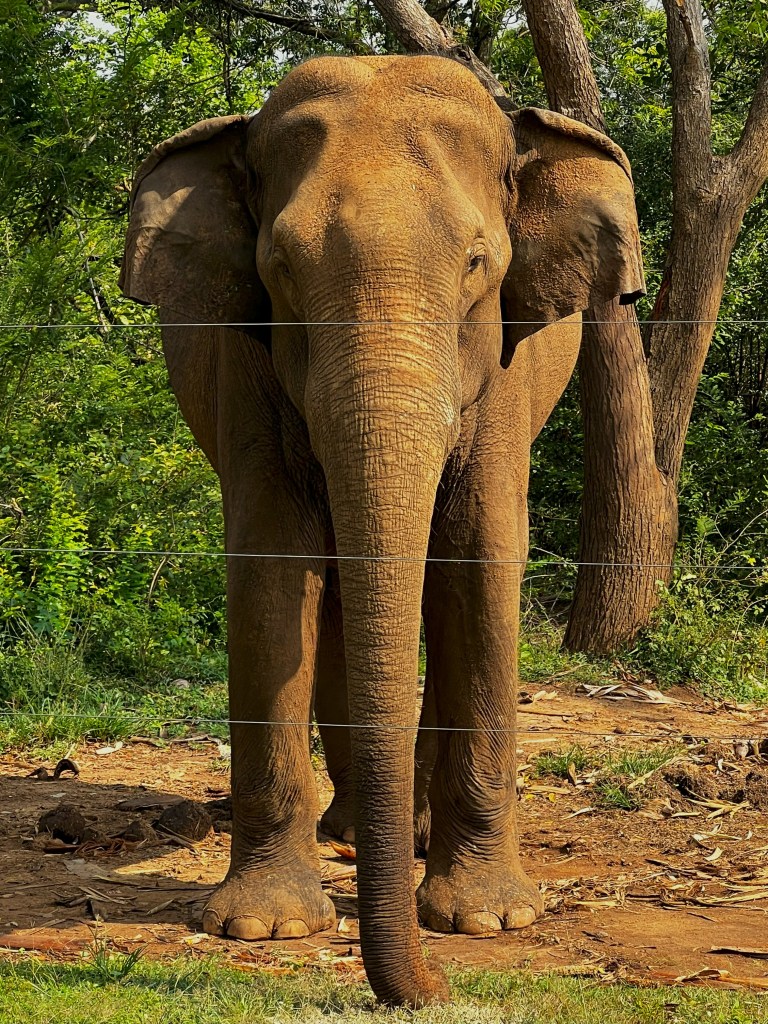

My research covers two locations with remarkably similar problems, even though an ocean separates them. Outside of Thailand’s Kui Buri National Park, farmers spend their mornings preparing pineapple fields for harvest, while across the Indian Ocean in Sri Lanka, farmers near Udawalawe National Park set out to monitor a variety of different crops. Though separated by thousands of miles, these communities share a common challenge: finding ways to thrive alongside Asian elephants in an increasingly crowded landscape.

As an elephant researcher working across these two distinct regions, I have a unique opportunity to compare how variations in historical contexts and cultural structures shape human-elephant interactions in real-time. While most scientific studies rely on comparing methods and results from published literature, our research teams simultaneously monitor these two sites to understand better how anthropogenic change, climatic variation, and regional stressors impact the complex and changing relationship between humans and elephants.

Research Sites and Local Partnerships

Our research spans two carefully selected field sites, each offering distinct insights into how humans and elephants are currently co-existing. In Sri Lanka, we work at a site established by Dr. Shermin de Silva in 2006, situated just outside Udawalawe National Park, which covers 308km2. Our Thailand field site borders Kui Buri National Park – a protected area more than three times larger at 969km2 – where our partners at Bring The Elephant Home (BTEH) have built strong community relationships over two decades. In both locations, Asian elephants and humans share resources, particularly in agricultural areas, but the historical context of these interactions varies dramatically.

A Tale of Two Histories

In Sri Lanka’s Udawalawe area, people have farmed alongside elephants for generations. The construction of the Udawalawe reservoir in 1972 led to the establishment of the national park. The area that became the park had primarily been a teak plantation rather than farmland, which meant that establishing the protected area didn’t require relocating large areas of farming communities – as can often be the case. The farmers who live around the park’s edges today are largely from families who have traditionally farmed the surrounding lands for generations, maintaining their agricultural practices and long history of living in proximity to elephants.

In contrast, Ruam Thai Village in Thailand represents a more recent human settlement. Established in the 1970s through a government initiative, the village brought together people from across Thailand to create a new community focused primarily on pineapple cultivation, two decades before the area would be designated as Kui Buri National Park in 1999. The crop’s high international market value made it economically attractive, and it also drew interest from local elephants. The tragic deaths of two elephants from poisoning and gunshot wounds in the late 1990s prompted His Majesty the King of Thailand to establish Kui Buri as a protected area specifically for elephant conservation. However, recent research by the Udawalawe Elephant Research Project (UWERP) and Trunks & Leaves team has revealed that elephants in both locations typically spend only about 50% of their time within national park boundaries, highlighting the critical importance of understanding and supporting coexistence in the surrounding landscapes. (See Annie’s blog on How Elephants in Sri Lanka Use Protected Areas here.)

These different historical trajectories have shaped distinct landscape patterns. Sri Lankan farms form a patchwork of individual plots interspersed with houses and fragments of forest, reflecting generations of land division and management. Ruam Thai’s layout is more structured, with a centralized residential area separated from a consolidated farming zone that borders the protected area.

Elephant Memory and Cultural Heritage

Over an elephant’s 60-year lifespan, they build up an extensive catalog of experience across a vast landscape. Due to the social complexity of elephant culture individual experiences become part of a vast assemblage of experiential knowledge that crosses generations. We’re discovering that elephant populations may develop distinct “cultures” influenced by their interactions with human communities over generations. In Sri Lanka, for instance, elephant family groups demonstrate sophisticated knowledge of traditional movement corridors that predate current human settlements. Meanwhile, in this area of Thailand, elephants show different patterns of adaptation to the more recently established agricultural landscape.

The concept of generational learning adds another layer to this complex relationship. Like humans, elephants can pass on behavioral responses to past experiences. In both locations, we’re observing how historical interactions influence current elephant behavior and how these learned responses might be transmitted to younger generations.

Pathways to Harmonious Coexistence

While the challenges in each location are unique, our ultimate goal remains constant: creating environments where both humans and elephants can thrive together. In Sri Lanka, this means building upon generations of traditional knowledge about elephant movement patterns. In Thailand, it involves developing new strategies that account for the more recent nature of human-elephant interactions.

Current initiatives in both locations show promise. Sri Lankan farmers are experimenting with crops less appealing to elephants that will allow them to use the same land, while maintaining historic elephant pathways through their lands. In Thailand, community-led initiatives in high-conflict areas are exploring converting pineapple fields to organic alternative crops that will reduce conflict and improve healthy farming.

Looking Ahead

As our research continues, we’re working to understand what successful coexistence looks like in these different contexts. Can the traditional knowledge of Sri Lankan communities inform new approaches in Thailand? Might Thailand’s community-centered development model offer insights for Sri Lankan villages? By studying these questions across two distinct cultural and historical settings, we hope to develop more nuanced and effective approaches to fostering positive human-elephant relationships.

The path to harmonious coexistence requires patience and understanding, but studying the shared histories of humans and elephants in each landscape provides crucial insights for future conservation efforts. As we continue our research, one thing becomes clear: successful conservation strategies must honor both the human and elephant histories that shape each unique landscape.

Our next stop was school teacher Shiromi’s home. We met with Shiromi who greeted us with her family and offered the most amazing homecooked treats. We chatted about her work in the village and her school, Dimuthu preschool. We met with Shiromi again the following day, where we observed the children in her classroom. The parents were very supportive of Shiromi and came to the school with their children even though they were supposed to be on holiday. We got to sing and dance the “hokey pokey”.

Our next stop was school teacher Shiromi’s home. We met with Shiromi who greeted us with her family and offered the most amazing homecooked treats. We chatted about her work in the village and her school, Dimuthu preschool. We met with Shiromi again the following day, where we observed the children in her classroom. The parents were very supportive of Shiromi and came to the school with their children even though they were supposed to be on holiday. We got to sing and dance the “hokey pokey”.