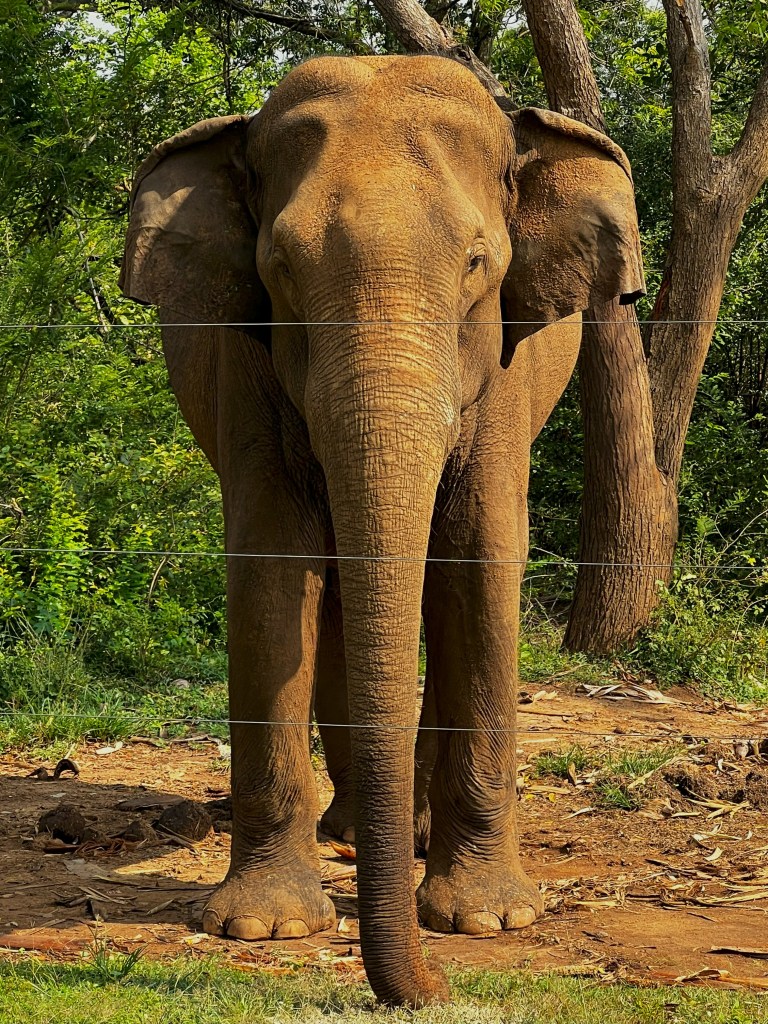

It’s a quiet morning at the southern boundary of Udawalawe National Park, Sri Lanka. The light is soft, dew clings to the fence posts, and tourists gather expectantly beside the electric line. In their hands, some corn and smartphones. On the other side, shadows shift into focus, a male, unmistakably massive and composed, stretches his trunk toward the fence in an imploring motion. The corn lands at his feet. He clenches it with his trunk. Cameras click. Children giggle. A perfect moment.

To the casual observer, it feels intimate and even harmless.

But behind this feel-good interaction lies a troubling truth. These elephants aren’t here for casual curiosity; they’ve learned that this fence means food!

Across the range of the endangered Asian elephant, an insidious conservation crisis is unfolding. New research published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence by Dr. Shermin de Silva and colleagues reveals the hidden dangers of this seemingly innocent practice. Tourists eager for memorable encounters feed elephants at roadside fences, safari parks, and forest edges. These seemingly well-intentioned actions are transforming how elephants behave, where they go, and how they survive.

Elephants are highly social and cognitively advanced animals, capable of social learning and cultural transmission (even of unhealthy habits) of behavior across generations. Once one elephant figures out that a certain location delivers easy – and delicious – calories from smiling humans, others quickly follow. These patterns persist across generations, becoming traditions; traditions that can get elephants killed.

Tour operators, driven by the promise of easy elephant sightings and happy tourists, have little incentive to stop the practice. And despite formal bans on feeding in most countries, enforcement is rare. As a result, a growing subset of elephants is becoming “food-conditioned,” often more daring, and ultimately more vulnerable.

This isn’t just an elephant problem. It mirrors issues with bears in North America, macaques in Sri Lanka, and marine mammals worldwide. Across species, food provisioning by tourists leads to aggression, habitat changes, disease spread, and often, death for wildlife and occasionally for people.

For a species like the Asian elephant, with fewer than 45,000 left in the wild, every behavioural change we cause has the potential to ripple into their future survival, and these risks are catastrophic.

The Rambo Effect: How One Elephant’s Habit Spread

In Udawalawe National Park, long-term elephant research has revealed the alarming impacts of tourist feeding. From 2007-2023, the Udawalawe Elephant Research Project (UWERP) identified 439 male elephants at the park’s electric fence-line (from a population estimate of 448-750 adult males). Of these, 66 individuals (9-15% of the estimated male population) were observed begging from tourists. Among them, one individual has become infamous: Rambo.

Rambo began “begging” from tourists before there was even a fence. Over 17 years, the UWERP team have consistently observed him at the same stretch of road, collecting fruit from visitors. For a time, he seemed harmless, passive, even endearing. Remarkably, even during musth, which is a heightened reproductive state in male elephants typically roam widely searching for estrous females, Rambo sometimes remained localized near the roadside feeding site.

The UWERP had long worried that tourists feeding Rambo sugary fruits like mangoes and bananas was having nagative consequence on his health, potentially leading to diabetes. Wild Asian elephants typically eat vastly more diverse, high-fibre, low-sugar vegetation. Rambo’s chrhonic eye discharge (noticed over ten years ago) may have been a sysmptom.

By 2020, everything changed. When tourism collapsed during COVID-19, Rambo began breaking fences and raiding nearby sugarcane fields at night. He even breached a power station compound. Local conservationists worked tirelessly to prevent his capture during this challenging period. Injured twice by people and potentially exposed to dangerous materials like plastic-wrapped fruit, Rambo exemplifies how food provisioning escalates elephant behavior into increasingly risky territory. His story reveals the complex social dynamics of male elephants and how human interference can disrupt natural behaviors. Tragically, he hasn’t been seen since April 2023; at the time, he was approximately 53 years old.

Wild male Asian elephants being fed along the park’s electric fence by local and foreign tourists.

After Rambo, other males followed suit. One died in a bus collision after fence-breaking. Another was shot. A third fell into a village well (although it’s unclear if he engaged in begging). And researchers have even found plastic bags in elephant dung near the fence. These are not isolated incidents; they’re predictable outcomes of long-term habituation. And the pattern is spreading.

India Experiences

In the Sigur region of India’s Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, a different experiment in food provisioning has unfolded over 15 years. Between 2007 and 2022, eleven male elephants were habituated by tourists and lodge operators who fed them sugarcane and fruits to lure them into view.

Four of those elephants died from causes linked directly to human interaction, including wounds, poisoning, and one fatal attack by resort staff.

The survivor with the most extraordinary story is Rivaldo, a tusker who lost a portion of his trunk to an explosive device. His trust in humans, cultivated through feeding, made it possible for veterinarians to treat him multiple times. But in 2021, citing safety concerns, officials captured Rivaldo and confined him to a kraal.

Public outcry and legal action secured his release. A structured rehabilitation effort followed, with forest guards monitoring him and preventing further provisioning. As of 2024, Rivaldo is thriving, being healthier, independent, and rarely entering villages.

When tourism halted during the COVID-19 lockdown, five of six surviving elephants also stopped approaching people. This natural pause showed that food-conditioned behavior is reversible, but only with strong intervention and community cooperation.

In early 2024, workers at a local lodge attempted to restart elephant feeding. They were caught and arrested, a clear sign that vigilance and enforcement are still urgently needed.

Feeding Fuels a Dangerous Cycle

Feeding wildlife isn’t new, and elephants aren’t the only species. Around the world, species from bears to monkeys to dolphins have suffered from similar human behaviors.

In Sri Lanka, toque macaques (Macaca sinica) have become emboldened and aggressive after years of tourist handouts. In Japan, macaques fed to reduce crop-raiding have overpopulated and caused worse conflict. In Yellowstone, food-habituated bears had to be killed. And in marine parks, dolphins and whales fed for entertainment have injured people and each other.

Animals copy each other. And in long-lived species like elephants, these behaviors can become cultural, passed from mother to calf, peer to peer. Once a population starts associating humans with food, reversing that behavior becomes difficult and dangerous.

Health risks add to the equation. Tuberculosis has been documented in elephants, and close contact through feeding increases disease transmission. Plastic ingestion, diabetes-like symptoms from sugary foods, and metabolic disorders have all been recorded in provisioned wildlife.

Feeding is never just about food; it’s about changing entire ecosystems.

Breaking the Cycle: Solutions That Work

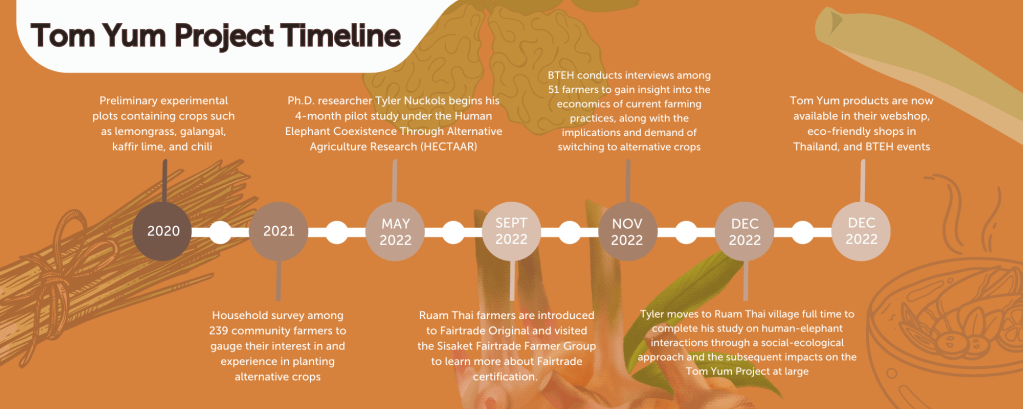

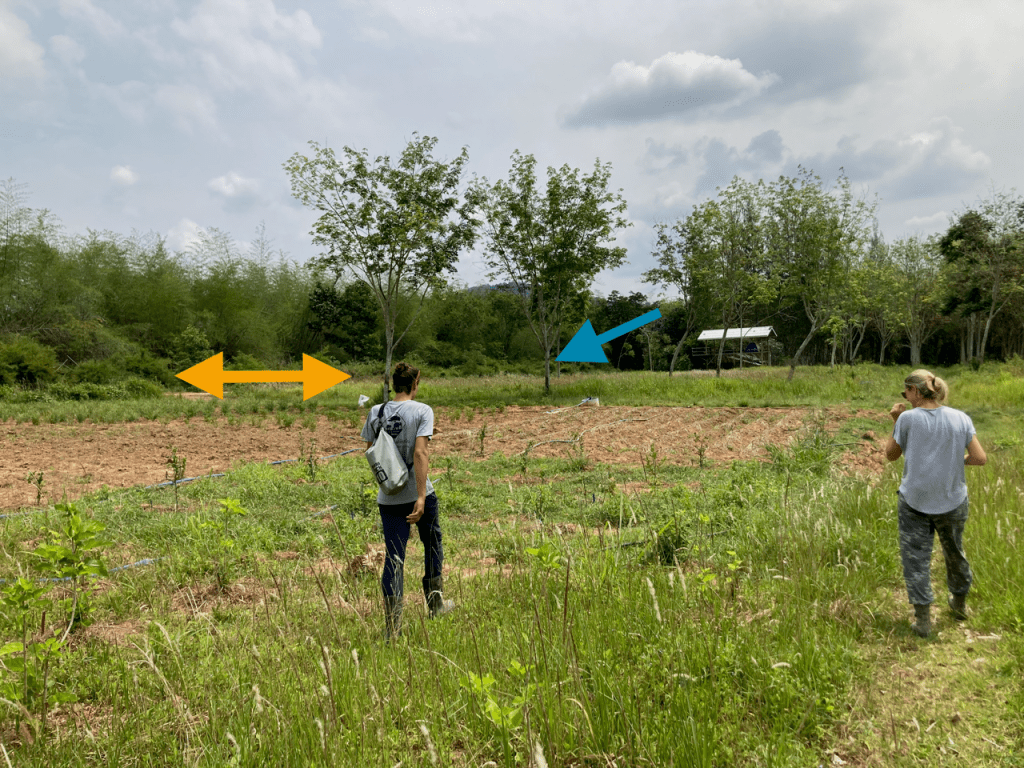

Across Asia, researchers and NGOs are showing that crops like chili, lemongrass, and citronella deter elephants while improving farm incomes. In Thailand, farmer participation in BTEH’s program is growing. In Sri Lanka, similar experiments are underway. A 2024 study found that these crops not only reduce conflict but also outperform traditional ones economically. When communities own the solution, coexistence becomes a shared goal.

It should also be considered that elephants need room to move. In Nepal, GPS collar data is helping map “elephant highways”, safe transboundary corridors between parks. This data-driven approach helps prevent tragic events like poisoned elephants found near towns. The future lies in maintaining landscape connectivity, not creating isolated “islands” of protected land.

Apart from all that, science must lead policy. Dr. Shermin de Silva’s book Elephants: Behavior and Conservation emphasizes the need to integrate elephant culture and cognition into management decisions. Multi-country collaborations, Trunks & Leaves, BTEH, and Forest Action Nepal are already modeling this shift.

Policy frameworks need to reflect behavior, not just boundaries. And tourism must be reimagined: not as a spectacle, but a tool for education and sustainable livelihoods.

Feeding bans alone aren’t enough. We need systems that support better choices.

What Can You Do to Help Today…

The solution isn’t complicated; it’s commitment. Here’s how you can make a difference.

Learn & Pledge: Understand what ethical elephant tourism looks like and take the pledge for responsible wildlife experiences.

Share the Knowledge: Read our comprehensive guide “Responsible Tourism & Ethical Elephant Experiences” and share it with fellow travelers.

Speak Up: When you see irresponsible feeding, report it. Your voice can save lives.

Support Solutions: Choose tour operators who prioritize elephant welfare over quick photo opportunities.

The Asian elephant is running out of time. With fewer than 45,000 left in the wild, every action matters.

Let’s ensure the next time a tourist points a camera at an elephant, it’s through a lens of respect, not regret.

Access the full paper here:

de Silva, S., Davidar, P., & Puyravaud, J.-P. (2025) Don’t feed the elephant: A critical examination of food-provisioning wild elephants. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 6 (3). doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.70060