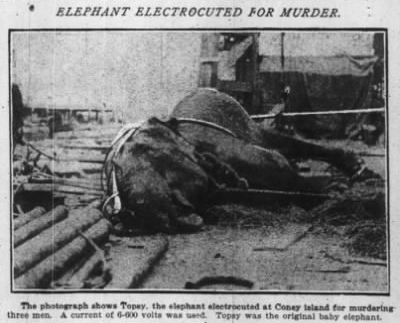

Baretail and Batik with their newborns.

We sometimes forget how fortunate we are to be able to watch peaceful, calm, habituated elephants in Udawalawe. It’s easy to take for granted when they stand there, threshing their grass en masse, as though it were the most natural thing in the world to have a horde of humans gawking at them from a few meters away. This post may seem self-evident to a younger generation of wildlife watchers, who have grown up in a world packed to the breaking point with human beings and who realize that wilderness is an increasingly rare and precious thing. But it may challenge the thinking of some, particularly those of an older generation, for whom wilderness was a vast and ominous space teeming with dangerous things. For the latter, seeing wildlife might satisfy the need for a thrill in the same way as watching a frightening movie or visiting an amusement park – especially if that wildlife acts fierce and ferocious, such as charging elephant might do. This view still prevails among more than a handful of people today, who might think that seeing the “tame” elephants of some national parks is not as much fun as getting a much more “wild” experience in more secluded areas where the animals elicit more mutual terror.

If this is you, or someone you know, then read on and share. This post is for you.

Loch Ness monster?