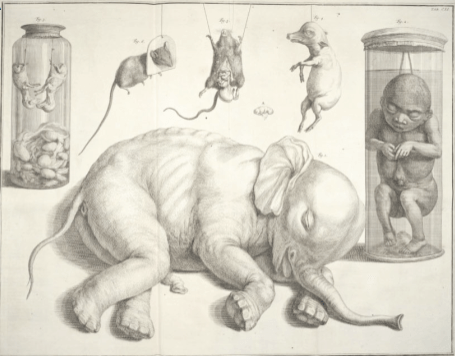

The Uda Walawe Elephant Research Project is now approaching eight years, a unique study of Asian elephants. Because elephants are such long-lived animals, it takes a long time to understand them – particularly for important variables like who reproduces and how often. Studies of wild African elephants have been conducted at multiple sites over 10 years or more (in some cases as many as 40!), but this has not been the case for the Asian species in the wild. There have been long-term records of Asian elephants populations in captivity from places like Myanmar, where they have long been used in timber camps, and it’s interesting to see how the two compare.

This past December we published a comprehensive paper analyzing six years of data on the wild Asian elephants of Uda Walawe National Park, Sri Lanka. This paper is one of a kind as it has been difficult for researchers to successfully monitor wild Asian elephants due to the difficulty of their habitats, and the logistical challenges of conducting steady research over longer time periods.

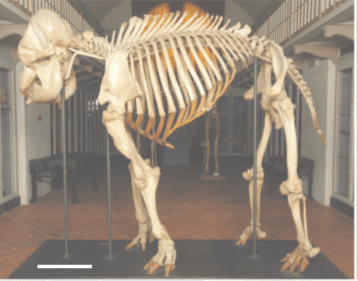

Tailless was one of the venerable elders of our population. She was especially important for this study for two reasons: she was unmistakable even after dying due to her uniquely broken tail, and her skull and jaw were recoverable. The wear on her teeth showed her age to be around 60 or more, meaning female elephants in Uda Walawe can potentially live out their full lifespans. We aged other females in the population relative to Tailless.